Why Zambia’s upcoming poll risks tipping the balance against democracy.

By Phumzile Mavimbela

Zambia is one of the fastest eroding democracies in the world. This is according to the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-dem), one of the most trusted sources of information on indicators of democratic progress or regression. The project’s 2020

report notes that Zambia has registered a remarkably rapid decline in the quality of democracy since the last election in 2016.

Nor is there great optimism about the next set of elections, due to take place in less than four months. Observers have serious concerns ahead of the polls. One of the main ones is about the quality of the

voters’ roll.

The electoral commission decided in 2020 to

scrap the voters’ roll that had been in use for over a decade. It then allocated just 38 days to register more than 8 million people in the middle of the rainy season.

The commission

has refused to make the roll available for an independent audit, ignoring widespread calls to do so. Such an audit of the roll was allowed in 2016.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.

Get newsletter

The limited information available in the public domain suggests that the registration process has indeed been skewed towards regions that vote for the ruling party.

2016 voting patterns and the 2021 register

Zambia appears to have become more politically polarised along ethnic lines since 2016. This is in part due to regional voting patterns which appeared – on the surface at least – to have split cleanly along ethno-regional lines.

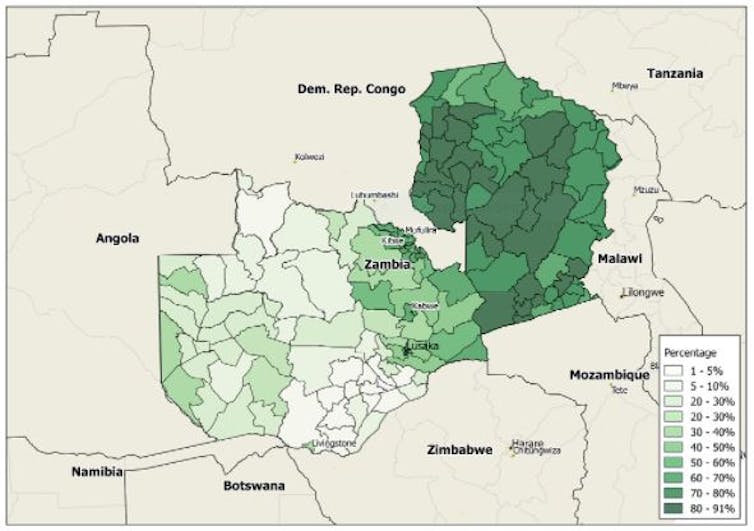

In 2016, support for the ruling Patriotic Front and President Edgar Lungu was drawn predominantly from the largely Bemba-speaking north and Nyanja-speaking east of the country. The Patriotic Front’s support has traditionally come from Bemba-speakers. But Nyanja-speaking easterners have rallied around the Patriotic Front following Lungu’s rise. He originates from the east, has backing from prominent Nyanja-speakers and has elevated easterners in cabinet and government.

Figure 1: The ruling Patriotic Front party’s vote share in the 2016 Presidential race. Author provided

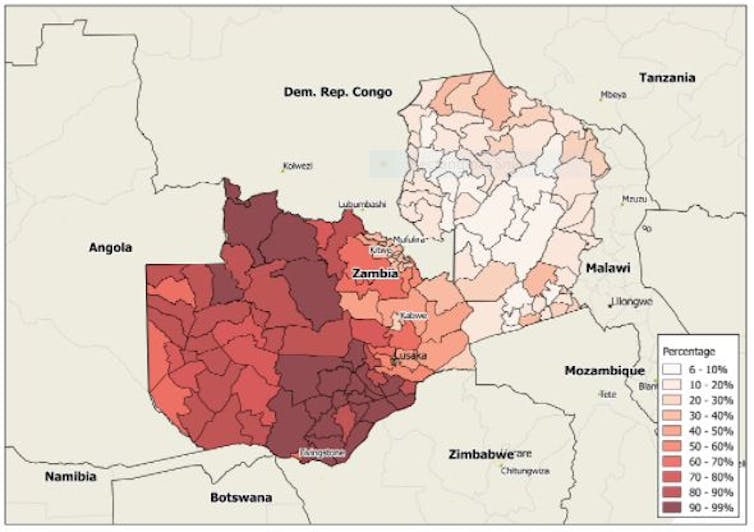

In comparison, the main opposition party’s support was drawn substantially from the Tonga-speaking southern and Lozi-speaking western regions. The so-called Bantu Botatwe (affiliated groups from the south and west) have long supported political parties that represent their economic and political interests, but these parties have never come to power or sponsored a president.

These regional patterns of support have not gone unnoticed in Lusaka. Since the 2016 elections, there has been a growing rhetoric of distrust from the ruling party towards the south and west of the country.

Senior members of the ruling party have increasingly made

disparaging remarks against citizens from those regions.

In addition, the cabinet and senior positions in the

civil service and

judiciary appear to have been skewed towards people who come from the north and east.

By comparison, there is almost no representation of people from the south and west of the country.

Crucially, an analysis of the new 2021 voters’ roll by Zambian academic Dr Sishuwa Sishuwa – recently

threatened with arrest for sedition by a key ruling party figure – suggests that significantly more citizens have been registered for the next poll in regions that support the ruling party. Meanwhile, far fewer voters have been registered in opposition-supporting regions.

These dynamics are important, and worrying. For a long time Zambia has had a policy of

regional balancing in key government appointments. This has largely held regional grievances

in check.

But perceptions of persecution of groups who have historically supported the opposition are deepening, and may well become more entrenched with the elections.

Figure 2: Opposition UPND’s vote share in the 2016 Presidential race. Author provided

Credibility gap

In 2016, Lungu cleared the 50% electoral threshold with just 13,000 votes, with Hakainde Hichilema

close at his heels. Given the clear disparities in the recent registration numbers across regions, it is difficult to interpret them as anything but an attempt to pack the voters’ roll with ruling party supporters. This also serves to disenfranchise opposition voters.

The reluctance of the electoral commission to subject the roll to an independent audit – as it did in 2016 – increases these suspicions.

The Catholic Church, a key player in the country’s politics, has expressed

deep reservations about the registration process. The Christian Churches Monitoring Group has also

highlighted major gaps and deficiencies with both the process and the registration rates.

Hichilema has

noted his serious concern with the register. This distrust of the election commission runs deep within the opposition, which may well lead to increased tensions ahead of and following the polls.

There are additional worries too. The government has used COVID-19 restrictions to curtail the

opposition’s ability to campaign. This includes

demonstrations or party meetings even in

private homes.

The electoral commission’s January statement appeared to suggest that movement restrictions during campaigns would be

enforced.

There’s increasing concern about heavy-handed tactics by the police who have repeatedly used excessive force to disperse opposition gatherings. Two people were killed in Lusaka late last year when police

opened fire on a crowd of opposition supporters.

Arrests for insulting or defaming the president have increased. Since March 2020, at least six people, including a 15-year-old boy, have been

arrested over such offences. This has reduced space for dissent alongside

shrinking space for media and non-governmental organisations wary of running afoul of the government’s agenda.

In 2019 the government set about trying to change the constitution to further strengthen the presidency relative to the judiciary and legislature. It

failed in late 2020, catching the administration by surprise.

In the wake of this, the ruling party introduced a new Cyber Security and Cyber Crime law. It has been roundly

criticised as failing to meet basic

human rights standards, further

shrinking civic space and placing whistleblowers and journalists at unjustified risk.

Looking ahead

The divide between the opposition United Party for National Development and ruling Patriotic Front continues to widen, and distrust runs deep. Concerns with the electoral commission’s management of the process have most outside observers worried about the diminishing likelihood of a fair election.

The increasing

impunity of ruling party-aligned “cadres” and their politicised accusations against

civil servants and citizens is a growing concern, as much of the violence surrounding the

2016 election was perpetrated by these groups of

young men who are sponsored by politicians.

Zambia’s status as a peaceful, democratic and free country is increasingly at risk. The 2021 election holds the potential to tip the balance if politicians aren’t careful and the international community pays little heed.

Article Tags

Africa

Africa Education

Education Joburg

Joburg South Africa

South Africa Greatest Africans

Greatest Africans Africa

Africa Education

Education Joburg

Joburg South Africa

South Africa Greatest Africans

Greatest Africans